To improve health equity for people of color, we need to address racism’s impact on health across medical and non-medical sectors. While it is important to explicitly highlight race/ethnicity and racism in the medical field and help health care professionals understand common mechanisms used to discriminate against people of color, it is also important for the medical field to contribute to efforts that highlight the health impacts of racism across non-medical sectors.

Studies show that non-medical socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioral factors account for a majority of health outcomes. Past and present discriminatory policies and practices that created inequities in social and environmental conditions are to blame for many poor outcomes experienced by Latinos and other populations of color today.

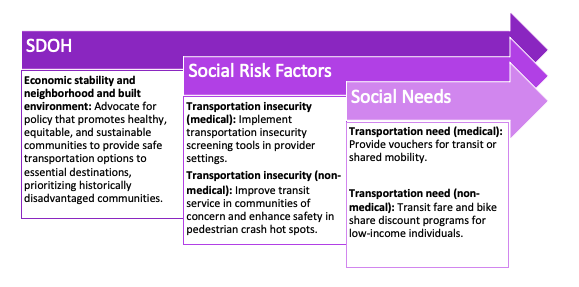

The pathway between inequities in social and environmental conditions and poor health outcomes are known as social risk factors, such as housing insecurity, income insecurity, and transportation insecurity. Because social risk factors are a consequence of racism and a contributor to health inequity, the medical sector plays an important role in educating the public about the effects of such inequities and supporting the non-medical sector in addressing the broader social determinants of health (SDOH) through upstream change (see Exhibit 1).

As communities across the country declare racism a public health crisis, the medical sector can contribute in three meaningful ways: focus on addressing the root causes of social risk factors while also addressing social and medical needs; establish and utilize tools to screen for the social risk factors that arise from systemic inequities that contribute to social need and poor health; and understand and overcome common mechanisms used to discriminate against people of color.

The idea that health is shaped by social and economic conditions is not new. However, the awareness that interventions are necessary to tackle social needs in patient care is only now entering mainstream health care. Finding solutions to deal with the root causes of those social needs is way behind. Addressing social needs in medical care is essential to improve health outcomes, but social needs are neither unique nor random. Systemic inequities rooted in a racist past result in the social risk factors that contribute to social needs, making it harder for Latinos, Blacks, and other people of color to stay healthy.

COVID-19 shined a harsh light on and further exacerbated systemic inequities, especially for Latinos. These inequities are particularly problematic because literature suggests there is a dose-response relationship between social risk factors and health; meaning, the more social needs a person faces, the higher their risk for worse health outcomes. For example, researchers assessed the rate of hospital readmission by the level of health-related social needs from ICD-10 Z codes (diagnosis codes for non-medical social needs that a patient may experience). The researchers found that among patients without codes in any of the five domains of health-related social need ─ including employment, family, housing, psychosocial, and socioeconomic status (SES) ─ 11.5% had a 30-day readmission. Among those with codes in one domain, 27% had a 30-day readmission, increasing to 63.5% for patients with codes in five domains. Of note, only 2.4% of the more than 13 million patients included in this study had at least one health-related social need.

This low number suggests inadequate screening practices because the unemployment rate was 4.4% the year the study was conducted, and the poverty rate was 12.3%, with drastic disparities by race/ethnicity for each measure. In 2017, the unemployment rate was 7.5% for Black people and 5.1% for Latinos compared to 4.2% for white people; and the poverty rate was 21.2% for Black people and 17.2% for Latinos, compared to 9% for white people.

Although ICD-10 Z codes are the primary tool for the medical field to standardize screening for documenting and coding social needs, adoption has been slow. In a cross-sectional study of U.S. hospitals and physician practices, only 24% of hospitals and 16% of physician practices reported having a system in place to screen for the following five social needs: food insecurity, housing instability, utility needs, transportation needs, and interpersonal violence. Of course, having a system is a far cry from using the system. In addition to concerns about low screening practices are concerns that ICD-10 Z codes are not granular enough. That’s why, in December 2020, after years of consensus building, The Gravity Project and several other organizations developed and submitted a proposal to the CDC National Center for Health Statistics ICD-10-CM Coordination and Maintenance Committee to replace the Z codes with 10 domains of social risk codes.

Without addressing the systemic inequities that cause the social risk factors that contribute to social needs, social needs will continue to arise in populations of color; and social needs will continue to return in patients who are the sickest, and as a result, require the most expensive care.

Efforts to address the impact of racism on health must be informed by a better understanding of the “causes of the causes” of health inequities, particularly a better understanding of how toxic stress undermines health and how inaccessible, inadequate, unaffordable, unreliable, and unsafe transportation undermines health. Additionally, efforts to address the impact of racism on health must focus on Latino families’ strengths and Latino contributions to urban space.

Another important target for the medical sector is implicit bias. Many studies show that physicians — especially white physicians — have implicit, subconscious preferences for white patients over patients of color. Implicit bias can lead to false assumptions and adverse health outcomes. For example, Latino men are less likely to get treatment for high-risk prostate cancer than white men, and white male doctors are less likely to prescribe pain medications to Black patients than their white counterparts. We must find new ways for health care providers to understand and overcome implicit bias as well as other mechanisms they use to discriminate against people of color.

Everyone has the capacity to try to uncover their own implicit biases. The national Salud America! program has a toolkit that guides people to reflect on their own implicit bias and learn from others who have overcome theirs. And we need health care providers to take the lead to educate their peers, like Dr. Jabraan Pasha, who created a training workshop to spread awareness of implicit bias in health care; and Dr. Chiquita Collins, who helped launch a new diversity training to empower UT Health San Antonio faculty members to recognize and speak out against acts of racism and discrimination.

The United States should have a goal to achieve health equity, where everyone has an equal opportunity to be their healthiest. That means we must address racism across medical and non-medical sectors. We need cities to declare racism a public health and safety crisis and commit to systemic change. Without a better understanding of the prevalence of social risk factors and recognition of the role discriminatory practices have played and contributed to social risk factors, health policies or initiatives may not be as effective as intended.

Therefore, we need health care leaders to play a role in screening for social risk factors, promoting awareness of the mechanisms behind discrimination of people of color and advocating for upstream solutions to address inequities in social and environmental conditions that contribute to social risk factors, particularly as we recover and rebuild from COVID-19.

Exhibit 1: Examples of transportation interventions across the continuum of social determinants of health (SDOH), social risk factors, and social needs in medical and non-medical settings. Although often overlooked, transportation issues are particularly important because so many families are transportation cost-burdened, especially those of color. These families forego other essentials like food and health care, which further threatens health, or are at risk of employment insecurity because they are dependent on others or unreliable mass transit to get to work.